Is it ethical to eat eggs at all?

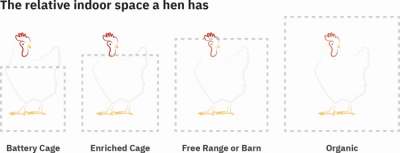

Globally, over 80% of the world’s hens, that’s over six billion, are housed in cages, mainly battery cages with a floor area less than a sheet of A4 paper. Battery cages were banned in the EU in 2012.

Over 12 billion eggs are eaten in the UK every year, and 86% of these come from the 40 million hens farmed in the UK. The remaining 14% come from other countries, including the US, Spain, and Poland.

For this guide to finding an ethical egg, we devised a bespoke rating looking at what the companies were saying about the welfare of the hens that supply their eggs. Spoiler: some brands scored zero marks for hen welfare.

Which egg brands and egg alternatives are in the guide?

This guide to eggs and vegan egg replacers includes:

- the UK’s two biggest egg suppliers (Noble Foods and Stonegate Farmers)

- supermarkets that sell own-brand eggs

- some smaller, specialist egg suppliers.

Noble Foods is the leading supplier of eggs for the major supermarkets’ own-brands and Stonegate supplies Waitrose.

Noble Foods sells under several different brands like Happy Eggs, Big & Fresh and many more. It's associated with some pretty awful conditions for hens and impact on the environment, which we discuss in the guide.

We’ve also rated four vegan egg replacers in this guide too, so if you're looking to reduce your egg consumption we've got you covered.

Can eggs be cruelty free?

There are animal rights and welfare issues associated with eggs, even ‘good’ ones like free range.

In this guide, we look at what free range actually means, how ethical it is, and why many campaigners argue that free range is not all that it’s cracked up to be. We also consider the unavoidable issue of male chicks and why the egg industry is far from cruelty free when it comes to killing day old male chicks in their millions.

Plus, there are environmental issues such as greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution from egg farms, and soya in the feed linked to deforestation in South America.

But the good news is that plant based egg replacers, and using alternative ingredients, are viable options. We compare the price and protein levels of these alternatives so that you can make informed choices of what to buy.