Labels for meat, dairy and eggs

Soil Association Organic

Soil Association’s Organic label is one of your best bets when it comes to eggs, meat and dairy. It is the strongest of the organic standards. Standards include:

- Access to pasture and space for all animals

- No routine use of antibiotics for all animals

- No beak trimming for chickens

- Five-times smaller chicken flocks than for free-range

- No tail docking or teeth trimming for pigs

- Fish must be killed humanely

Organic

Other organic standards can vary but standard requirements include:

- Animals should be grazed outside for most of the year (weather permitting)

- Minimum weaning age for calves is 12 weeks

- The routine use of antibiotics is prohibited

- Artificial pesticides cannot be used on the land

- No use of GM feed

- For eggs, Soil Association is certainly the best of the organic bunch

Pasture For Life

Pasture For Life (PFLA) is another of the strongest options, established by the farmer-led Pasture-Fed Livestock Association. The organisation champions the benefits of dairy (beef and lamb) production just from grass and pasture, with no grains being fed to the animals.

The Pasture for Life standard currently only applies to cow’s milk, beef and lamb, and its notable requirements include:

- No zero grazing

- Prohibiting the use of soya and GM animal feed

- Minimum weaning age for calves is 12 weeks

- Calves must not be killed (by the Pasture for Life farm) for any reason other than non-recoverable illness or injury

- Antibiotic use is kept to a minimum and reviewed on a case-by-case basis

Pasture Promise

Pasture Promise is another option focused on outside grazing for dairy products, but CIWF reckons that it offers a lower standard than Pasture for Life. Legally, free-range milk is yet to be defined and so The Free Range Dairy Network has developed their own working definition: the network requires its farmers to graze their cows outside for 180 days and nights a year (except in exceptional circumstances) before they can use the Free Range Pasture Promise logo on their products. They also prohibit free range dairy farmers from shooting calves unless it is ‘to alleviate pain or suffering’. No information could be found regarding this standard’s approach to antibiotic use.

Free Range

Unfortunately, Free Range is not quite the promise of open space and prancing lambs we often imagine. Welfare standards can vary wildly between different free range producers, from small-scale egg farmers with hens in a field to industrial producers who adhere to the minimum standards.

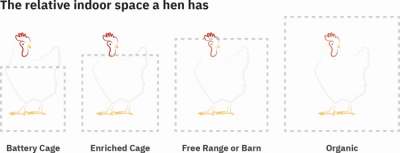

For eggs, the minimum standards mean that many free range hens are kept in vast, multi-tiered sheds typically with 16,000 or more other birds, few of which ever see daylight. They must be given some kind of daytime outside access, but in such confined spaces only few birds are ever able to actually make it outside.

Animal welfare organisations CIWF consistently places free range amongst the lower assurances for animal welfare across all sectors.

RSPCA Assured

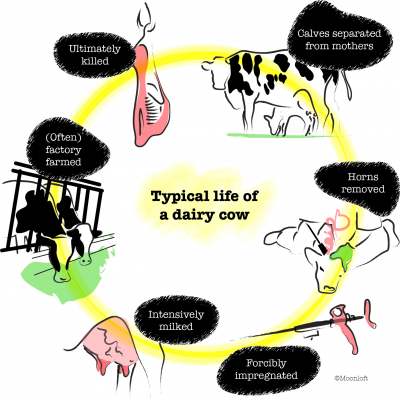

RSPCA Assured is slightly higher than the legal minimum. For example, for dairy cows a local anaesthetic is required when disbudding horns; embryo transfer and ovum pick-up are prohibited except in exceptional circumstances and outdoor grazing is encouraged. Antibiotics use is monitored and should be used only when ‘necessary’, with preventative measures being encouraged. Fish must be killed humanely. The use of GM animal feed is not prohibited.

However, there are many critics of the RSPCA Assured scheme. 60 animal welfare organisations plus politicians and celebrities have called for an immediate end to the scheme accusing it of “welfare-washing animal cruelty and misleading the public” in an open letter to the RSPCA. Chris Packham and Caroline Lucas have resigned as Presidents of the RSPCA, and Brian May resigned as vice president.

In 2024 the RSPCA announced that it would review the scheme and would make unannounced visits to 200 of the 4,000 farms covered. In October, their review was published and concluded that the scheme is “operating effectively to assure animal welfare on member farms”.

Red Tractor

You can basically ignore Red Tractor when it comes to animal welfare standards. It just means that the animal lived in the UK and was treated in line with minimum legal requirements.

CIWF says: “Some of the standards benefit animal welfare by going beyond minimum legislation, such as prohibiting castration of meat pigs, a slightly reduced stocking density for meat chickens and the requirement for on-farm health and welfare monitoring. However in some circumstances the standards inadequately reflect the legislation, such as provision for manipulable material for pigs, and do not address welfare issues not reflected in legislation, such as confinement of sows during farrowing and permanent housing and tethering of dairy cows.”

There have been multiple scandals involving the Red Tractor label in recent years. For example, in March 2025, campaign group the Animal Justice Project released footage showing cows being kicked, punched, and struck with bars and electric goads, and standing in ankle-deep water at a Red Tractor certified farm.

A spokesman for Red Tractor told Farming Weekly that within eight hours of receiving the footage, an independent assessor was on the farm to investigate this “unacceptable behaviour by farm workers”.

“This inspection confirmed all individuals identified mistreating animals no longer work on the farm,” it stated, adding that all current employees would be required to undergo additional training and further investigations were ongoing.

For more information about what these various standards mean in each sector, check out our article on dairy standards and our shopping guide to eggs.

Individual labels

In 2022, Arla – the biggest dairy company in the UK – announced the launch of its C.A.R.E. standards, standing for Cooperative, Animal Welfare, Renewable Energy and Ecosystem. However, as of 2024, the company still does not appear to have published the criteria for its standards online, making its claims that they are an “industry-leading requirement” look pretty empty.