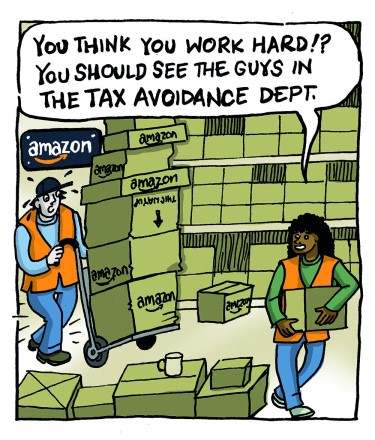

1. Amazon's tax avoidance

We estimate that Amazon's tax avoidance could have cost the UK economy around £575m in 2024.

Ethical Consumer has calculated that, in 2024 over half a billion pounds (£575,000,000) could have been lost to the UK public purse from the corporation tax avoidance of Amazon alone. This amount could have paid for:

- additional winter fuel payments to help with rising fuel bills, or

- additional nurses, or

- home insulation installations.

Amazon is paying a fraction of what it owes

Amazon publishes limited information about its finances. Estimating the total amount of tax the company should have paid is therefore a difficult task.

However our figures suggest that Amazon should have paid around £575m in 2024. According to the most recent figures, because of its aggressive tax avoidance strategies, Amazon is likely to pay around £18m, a tiny fraction of the amount that might be expected.

Amazon has recently been making a lot of noise about how much it raises in other taxes like VAT and National Insurance for the UK economy. Yet, in reality, any shop would have to pay these amounts: by replacing other independent stores (remember the high street?) Amazon is not increasing the overall amount paid to the public purse. It is instead taking business away from companies that would have paid some corporation tax on their profits as well.

Amazon is helping to build an economy where not everyone contributes to vital public services. Instead excess profits fund the laughable vanity projects of its billionaire owner in a time of crisis such as space rocket rides for celebrities…

The same old story

Over the years, we have repeatedly told the same story, with headlines like ‘Amazon’s UK tax up just 3% despite surge in profits’ in October 2020 to ‘Amazon’s tax bill falls despite tripling profits’ in September 2018. In 2019, Fair Tax Mark named Amazon as having “the poorest tax conduct” of the six major tech companies – a sector known for its tax avoidance.

In 2023, The Guardian stated that Amazon UK Services received tax credit of £7.7m for investment in infrastructure to year end 2022, and as a result, paid no corporation tax for the second year in a row, although other parts of the group’s UK business did pay an undisclosed amount. Amazon UK Services employs more than half of the group’s UK workers.

Also according to the Guardian, the profits and sales across Amazon's entire UK network rose to £24bn in 2022, making it bigger than Asda, the UK’s third-largest supermarket, and about twice the size of Marks & Spencer,

Amazon has been criticised for its tax practices in many parts of world, from the EU to the US. In 2018, for example, the company helped kill a new tax law in Seattle aimed at tackling homelessness – which had reached a ‘state of emergency’ in the city – after it threatened to pause local investment if the law went ahead.

Globally, the tax avoidance of Amazon and other companies costs US $245 billion a year. The impact is disproportionately felt by poorer countries.

As Athena Coalition – a US organisation of local and national groups opposing the online giant – writes:

“It’s we who should decide what is best for us in our communities — not big corporations. We can stop Amazon’s sweetheart tax deals from local governments, draining of public resources, and big-footing into our neighborhoods with no regard for the rest of us.”

So how is it avoiding so much tax?

Amazon has shunted much of its UK income to its subsidiary in Luxembourg, “where there is a ‘loss-making’ subsidiary that is not only not paying tax, but is generating enormous tax reliefs that can be used in the future to ensure that little or no tax continues to be paid,” according to Paul Monaghan from the Fair Tax Mark.

In fact, a report by Unite the Union in August 2021 found that the company may have shifted as much as £8.2 billion from the UK to Luxembourg in 2019. In 2017, the company registered almost 75% of its UK sales through the subsidiary.

The company has also sometimes shunted its remaining profits through time: Amazon has invested in dominating the market, thereby monopolising industries while keeping its profits low. This way, it can defer paying taxes until another time.