Cotton from the Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region

The human rights violations of the Chinese government in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are well-documented. According to The Coalition to End Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region, “abuses include arbitrary mass detention of an estimated range of 1 million to 1.8 million people and a program to ‘cleanse’ ethnic minorities of their ‘extremist’ thoughts through re-education and forced labour.”

The Chinese state is using forced labour as part of this system of control. Over half a million Uyghur workers have been forced to act as cotton pickers, after being released from ‘re-education camps’.

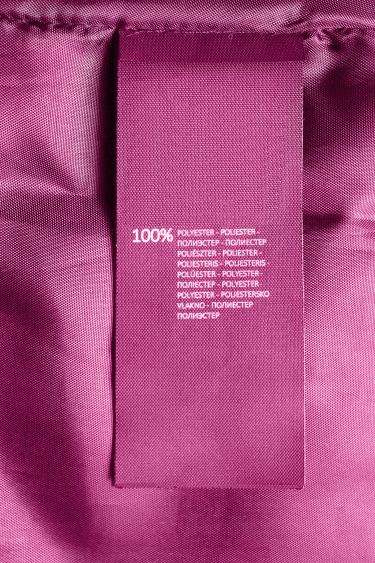

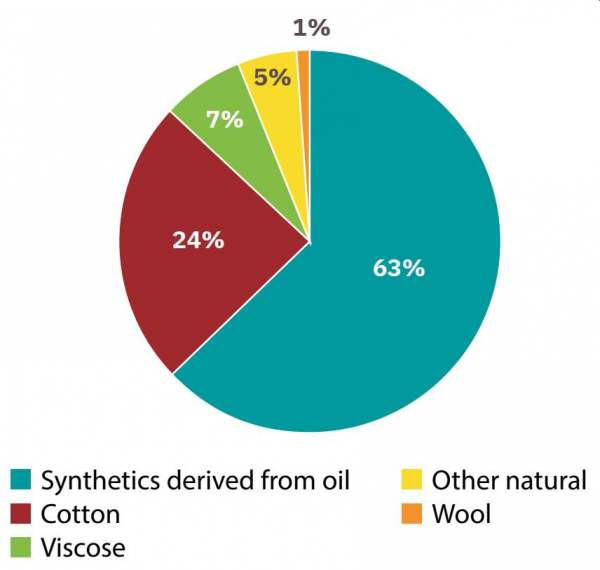

The Uyghur Region produces around 20% of the world’s cotton, and studies suggest that around 1 in 5 garments around the world are linked to this forced labour. “Almost every major apparel brand and retailer selling cotton products is potentially implicated,” the End Uyghur Forced Labour (EUFL) Coalition says.

The Coalition is calling for brands to exit the Uyghur Region. “The only way corporations can ensure they are not unwittingly bolstering the government’s repression is to fully extricate their supply chains.”

Among the brands in this guide, the following were listed by the Coalition for having committed to its Call to Action, and made their commitments public:

- ASOS

- Marks & Spencer

- Reformation

Research finds cotton from the Uyghur Region is found around the world

Sheffield Hallam University published a report in 2021 titled ‘Laundering Cotton’, which tracked shipping data and detailed, link by link, how cotton from the Uyghur Region is very likely to make its way onto shop shelves around the world.

Laundering Cotton: How Xinjiang Cotton is Obscured in International Supply Chains, investigates the supply chains of major clothing brands. The report found that many brands are running an extraordinarily high risk that the garments they are importing to the U.S. contain cotton from the Uyghur Region, which, if the case, would be in violation of an import prohibition imposed by the U.S. in January.

The report identifies 53 contract garment suppliers—in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Vietnam, India, Pakistan, Kenya, Ethiopia, China, and Mexico—that purchase fabric and yarn from five leading Chinese manufacturers that use Uyghur Region cotton. The suppliers use the fabric and yarn in the clothes they make for leading apparel brands, with no indication to consumers of the cotton’s origin. 103 well-known international brands are supplied by those intermediaries and are thus at high risk of having Xinjiang cotton in their supply chains. Brands named include Adidas, Nike, Levi's, Marks & Spencer, Patagonia, Primark, Gap, H&M, Decathlon, Jack Wolfskin, PVH Corp, Tesco, River Island, Topshop, VF Corporation, Ikea and Uniqlo.

“This report details, link by link, how some of the world’s most well-known fashion brands are very likely selling products produced with Uyghur forced labour to unwitting consumers,” said Louisa Greve, Director of Global Advocacy at Uyghur Human Rights Project.

“This pioneering research makes it clear that only through a firm commitment to exclude Uyghur Region cotton can brands provide any meaningful assurance to consumers and regulators that they are taking all the steps they can to remove the risk from their supply chains. This report leaves leading apparel brands, from Anthropologie to Uniqlo, with nowhere to hide.”

Legislation is now helping tackle Uyghur cotton and forced labour

In June 2022, a new forced labour ban was implemented in the US, which means that if there’s any reason to suspect that clothing being imported comes from forced labour it will be refused entry at the border. Any company wanting to import cotton from the Uyghur Region must show it was not made with forced labour (which is impossible to show), therefore it’s an incredibly effective law.

Similar forced labour laws are now being advocated for in the EU and other countries, and it’s hoped this will make it similarly difficult for forced-labour sourced clothing to find a market – including anything from the Uyghur Region or Turkmenistan.