This article includes:

- What is included in the supply chain of a mobile phone?

- What is supply chain management

- Ethical issues in supply chain management

- Electronic companies with ethical supply chains

- The benefits of an ethical supply chain

In this article we’ll look at some issues found in the supply chain of technology companies. We have used the example of a mobile phone supply chain.

This article includes:

A mobile phone has an extremely complex supply chain that is basically made up of three areas:

What are smartphones made of?

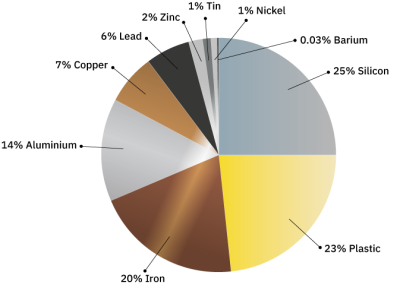

The composition of phones varies depending on the brand, but an average materials list for a smartphone is: 25% silicon, 23% plastic, 20% iron, 14%, aluminium, 7% copper, 6% lead, 2% zinc, 1% tin, 1% nickel and 0.03% barium.

At the bottom of the supply chain is the raw materials extraction, such as metals and metal ores. The raw materials are used to make the basic components of a phone. Often the raw materials are from mines with poor environmental records, whose profits are sometimes linked to armed conflicts and that have little or no protection of workers' rights.

China is one of the world’s largest suppliers of raw materials for electronic products. However, lax environmental and social regulations have led to its mining industry being heavily associated with environmental degradation and poor working conditions.

For instance the mining of 'rare earth elements' in China has left toxic lakes in Inner Mongolia and contributed to the contamination of farmland and air pollution, leading to severe public health risks – especially respiratory illness, skin diseases and cancer.

Several minerals have also been linked to the ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Referred to as conflict minerals, the supply chains of tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold are now subject to US, EU and Chinese regulations which aim to prevent the profits being used to fund armed groups in the DRC and surrounding countries. Mining in the DRC is also rife with labour rights' violations such as child labour and forced labour as well as bribery and corruption at a governmental level.

Ethical Consumer rates all electronic companies on their conflict minerals policies. For more details see our feature on conflict minerals.

The next few steps in the supply chain require manufacturers to transform the raw material into a usable material or component.

The end product is made up of many different components each with its own supply chain.

A basic smartphone is comprised of the following components:

Component suppliers are numerous and will often specialise in particular parts which may be used by many different brands.

An iPhone, for example, contains components from more than 200 suppliers. This is usually part of the supply chain companies have the least control or knowledge about due to the number of manufacturers involved.

Incidents of labour violations are not uncommon. In 2018 China Labour Watch (CLW) reported that component manufacturer to Apple - Catcher Technology (Suqian) Co Ltd based in Taiwan – had committed several labour rights' violations. CLW identified major issues at Catcher regarding occupational health and safety, pollution and work schedules. This included a toxic gas poisoning at Catcher’s A6 workshop, in May 2017, which resulted in the hospitalisation of 90 workers, with five workers admitted to intensive care.

An earlier investigation by CLW at Catcher Technology in 2014, found a string of rights' violations including discriminatory hiring policies, lack of safety training, long work hours, and low wages.

Once the components have been sourced from manufacturers they are taken to a factory for assembly. In China the largest company to assemble components for electronic companies is Foxconn. The iPhone is famously made at its Zhengzhou facilities in China. According to the New York Times, it takes 94 production lines and about 400 steps to assemble the iPhone.

The company has been linked to workers' rights abuses which in 2010 led to numerous workers committing suicide due to the harsh working conditions. Since 2010 Foxconn, and brands which it supplies, have been working together to improve conditions inside its factories. But, a 2015 report by campaign group SACOM reported that conditions were still far from being satisfactory.

It found:

SACOM urged Foxconn to:

Supply chain management is the way in which a company guarantees that workers’ rights and provisions are being met throughout the supply chain outlined above.

There are many different ways in which a company might set about achieving this. Most companies rely on contracts or codes of conduct with their 1st tier suppliers which list the provisions for the upholding of workers' rights. A 1st tier supplier is a company that provides parts and materials directly to a manufacturer of goods eg directly to Apple.

1st tier suppliers are often those suppliers who assemble the final product. Often companies will require 1st tier suppliers to ensure workers’ rights are guaranteed by the suppliers supplying components to the assembly factory, thereby absolving the main company of the responsibility.

However over the past ten years, companies have recognised that many workers’ rights violations occur further down their supply chains and therefore have extended monitoring and auditing processes to include some of those suppliers. It should be noted this is not done by all companies.

For all companies producing physical goods Ethical Consumer expects it to have a supply chain management policy. We then rate each company against a set of criteria. These criteria assess its policies as well as how it implements its auditing strategy, what stakeholders it works with to verify labour standards and how it addresses difficult issues such as illegal freedom of association.

Ethical Consumer’s supply chain management policy rating is broken up into four parts:

To achieve a best rating companies must be adequately addressing issues listed in each section.

Many companies will say that they do not want workers’ rights to be violated within their supply chain, however we know that workers’ rights are often violated. The electronics industry is a key example of where prominent brands such as Apple and Samsung will make firm commitments but in reality working conditions and practices do not change.

It is therefore important to consider why this might be.

1. Many companies have different definitions of workers’ rights. A supplier therefore might be supplying goods to lots of different brands who all define workers’ rights differently. A prime example of this would be clauses relating to working hours. Some companies may state that working over 12 hours overtime is allowed as long as it is not done on a regular basis whereas others will strictly prohibit it.

2. Audit fraud and fatigue. Companies often rely on audits to ensure suppliers are adhering to their codes of conduct however a supplier which has multiple customers will also end up being audited multiple times. This is known as audit fatigue where a small supplier's time is taken up by filling in forms and allowing inspections of its factories. There are initiatives which try and address this, for example SEDEX where suppliers can submit one audit review and then customers of that supplier can use that one audit. However this has its own problems.

Audit fraud can occur when suppliers know that audits are going to occur and hide “violations” away or tidy the factory. For example it is reported that suppliers who are notified of inspections may ask employees who are underage to not work on that day.

3. Failure to achieve standards set out in a company's code of conduct. A good example of this is payment of a living wage. Currently, there is no agreed definition of living wage for workers within the electronics industry - mainly due to the fact that basic needs always differ and vary from country to country. While there are several organisations working with companies to define and resolve this issue many electronic industry workers will receive far below what is considered a living wage. The failure to achieve living wages is complex but companies can show commitment to achieving this by joining collaborative initiatives with trade unions, other companies and NGOs.

4. Country laws and regulations. In most countries the right to freedom of association is guaranteed by law and provides workers with the right to be represented so that issues such as wages or overtime can be collectively agreed upon.

Yet in some countries the right to freedom of association is restricted. In China for example, all unions must belong to the state-controlled All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). According to Freedom House – which monitors freedom and democracy – the ACFTU functions more as an arm of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and is used to control workers rather than as a genuine vehicle for representing their interests.

Currently in our guide to mobile phones only Fairphone receives Ethical Consumer’s best rating for its supply chain management.

Apple's iPhone and Motorola scored a middle, and all others received worst ratings.

Ethical supply chains work for people and the environment in two basic ways:

In many countries, national laws protecting workers’ rights are very weak: much weaker than international human rights laws or conventions demand. Child labour from the age of 14 is in some places permitted, unionisation banned, or certain forms of bonded labour allowed. Even when suppliers are actually breaking the law, many governments lack either resources or the impetus to enforce penalties.

For workers, then, ethical supply chains are not just beneficial but vital. At the very minimum, they protect human rights. At their most effective, they incentivise suppliers to go beyond the baseline: for example providing child care, paying a decent wage, or giving education and training.

The same principle applies in terms of the environment. Many practices that cause serious environmental harm are legal or the authorities will turn a blind eye. But ethical supply chains alter the economic incentives. They make environmentally unsustainable practice economically unsustainable too. For example: if companies with ethical supply chains all selected green energy suppliers, coal and oil companies would increasingly lose out. The fossil fuel industry would become unviable.

More effective ethical supply chains will again go above and beyond this. They will disincentivise processes that put a long-term strain on the natural world, such as the ongoing use of agrochemicals.

This pressure can have a ripple down effect: if companies ask suppliers to have ethical supply chains too, respect for workers’ rights and the environment will spread through the supply chain as a whole.

But it is not only the environment and workers that win. Aside from the ethical obligation not to fund abuses, companies themselves can benefit.

It is increasingly normal for companies to consider ethical and reputational ‘risk’ in financial projections for the following year. This shows that abuses in a supply chain come with a real financial cost. If NGOs or the national press discover problems in a company’s supply chain, that company can take a real hit. Ethical supply chains protect companies from losing their reputation in this way, and all of the customers and profit that go with it.

All the information and inspiration you need to join thousands of others and revolutionise the way you shop, save and live. Full online access to our unique shopping guides, ethical rankings and company profiles. The essential ethical print magazine.