Two years ago, I was 17 and doing my A-Levels when I read that a charity that sends period products to Kenya was asked to divert supplies to a school in Leeds.

Girls were missing school because they were too poor to afford menstrual products, and teachers, having noticed a pattern of absences, quickly recognised that intervention was needed.

What emerged in the following days was news that this wasn’t confined to Leeds, it was happening all around the country, and hundreds of schoolgirls were compromising their education and falling behind in their learning, all because they were too poor to buy menstrual products.

Everyone was shocked and disgusted that period poverty was happening in the UK, but I was angry.

I was angry that the government hadn’t even acknowledged it. I was angry that, in the days that followed, the Education Minister, Justine Greening, refused to answer a question in Parliament about it, and I was angry that the plight of these girls, my age or younger, were being ignored as if they didn’t matter.

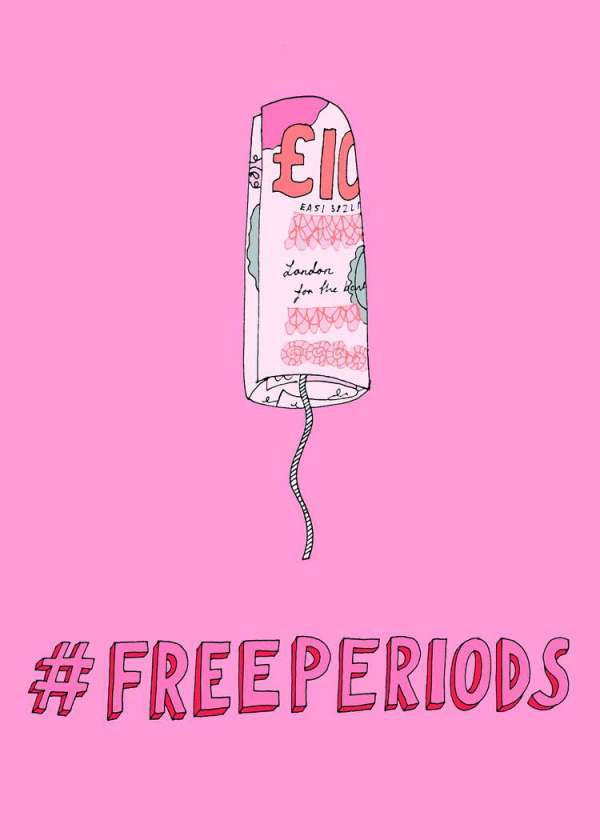

They did matter. I decided to start a campaign to lobby the government to provide free menstrual products in schools. I called it FreePeriods and started contacting MPs, media, schools, teachers, whoever would listen. I started giving talks, writing in newspapers, organised a protest, met up with MPs in Westminster, and did everything I could do to raise awareness of period poverty.

I started getting emails from girls who would tell me desperately sad accounts of how period poverty was affecting their lives; some of their parents had to choose between feeding their kids or staying warm, and some would tell me how they wouldn’t even ask their parents for money for pads. They knew there wouldn’t be any and they just didn’t want their parents to feel terrible by saying no.

Some would comb every inch of the house searching for pennies to pull together to buy a packet of pads, most often without any luck, sometimes relying on friends or teachers, sometimes not telling anyone and just staying at home instead of going to lessons.

This is the reality, and this is happening on our doorsteps. As a society, we should be ashamed. One in ten girls cannot afford menstrual products, 12% have admitted to making their own, and 6% of parents confessed to stealing them for their daughters.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights says that the right to an education is one of our fundamental human rights. Our periods should never be a barrier to accessing that right.

With the government’s Spring Statement pledge to end period poverty in schools by providing free menstrual products in all secondary schools and colleges in the UK from Spring 2020, that should never, ever happen again. In April, that pledge was extended to primary schools.

Other initiatives

A number of brands in our guide to sanitary products discuss the issue of period poverty in blog posts.

- The company Hey Girls was set up specifically to help reduce period poverty with its ‘Buy One, Give One’ scheme. For every pack of menstrual products you buy, Hey Girls gives one to women or girls who struggle to afford them. So far the company has given away well over three million packs.

- Bloody Good Period provides menstrual products to asylum drop-in centres and aims to start providing to food banks as well. Find out more at www.bloodygoodperiod.com.

- The Red Box Project provides period supplies to schools, including pads and tampons but also spare tights and pants. Find out more at redboxproject.org.

- Action Aid campaigns to end period poverty around the world. You can donate to projects such as helping local women learn how to make safe, re-usable sanitary pads, and then distributing them for free to girls at school – www.actionaid.org.uk/donate/period-poverty

- Freedom4girls – “The funds you donate will go towards the supply of disposable sanitary pads, mooncups, as well as washable reusable sanitary packs for schools and women’s agencies in the UK as well as worldwide” – www.freedom4girls.co.uk