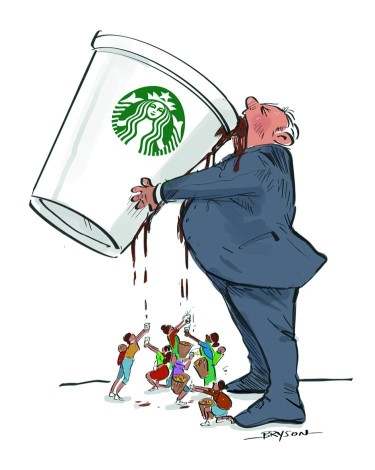

This standard is unique for its focus on pricing. Some of the reason for that is historical – it was stepping into the void left by the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement in 1989. The agreement had regulated how much coffee each country was allowed to export, stabilising prices and keeping them reasonably high. It was partly a product of the cold war: the US was frightened that Latin American coffee producers would turn to communism if they were too immiserated by low, volatile coffee prices. Its collapse led to a huge drop in coffee prices which threw many coffee farmers into poverty.

Volatile prices are very destructive for poor farmers, as it means they cannot know when planting crops what the price will be at harvest, and they cannot insure themselves against risk like bigger players. Fairtrade thus has a minimum price that must be paid when the market price falls below it, as a safety net. It also has a fixed premium that must be paid on top of the market price.

To complement this, regulations were added. To get certified, a producer must show that it is meeting certain social and environmental standards. It can then attempt to sell its produce at the Fairtrade price, if it can find a buyer.

That last point is a bit of a snag, however, and a common cause of confusion. Being certified Fairtrade does not mean that producers are selling their produce as Fairtrade. Certified tea producers on average only manage to sell around 7% of their tea on Fairtrade terms. The average across all products is about 40% for small farmer organisations, and 20% for estates. This has generated criticism, because producers need to recoup the certification cost and, in the worst cases, failure to sell much at the Fairtrade price may eliminate any benefit they get from being certified.

Fairtrade certifies both estates and cooperatives of small farmers, although ‘cooperatives’ does not necessarily mean small. The Fintea Growers Co-operative Union, for example, a tea growing coop in Kenya, has over 12,000 farmer members.

The Fairtrade premiums are currently set at US $0.50/kg tea, and $0.20/lb coffee. The market prices, meanwhile, are at around $2.60/kg tea, and $2/lb coffee. So currently the tea premium is around an extra fifth on top of the market price, and the coffee premium about a tenth.

The coffee price fluctuates more wildly that the tea one and has much more frequently gone below the Fairtrade minimum price. The premium is to be spent on community projects and, in the case of coops, how it is spent is supposed to be decided democratically.