4 things to think about when buying second-hand clothing

Second-hand clothing shops are abundant - whether that’s charity shops, vintage shops or second-hand apps like Depop. Buying-second hand is becoming more and more accessible, so here we give some top tips on what to consider and pitfalls to look out for.

1. Have you checked the fit?

It can be so disappointing to order the perfect-looking item second-hand and then find that it doesn’t even vaguely fit. While second-hand apps and websites will give you a label size, this can mean something very different depending on the brand.

If you’re buying direct from a seller, for example through eBay or a second-hand app, you probably won’t be able to return it, so it’s worth spending a moment working out the fit. There are a few easy ways to do this:

- Ask the seller to send a photo of someone wearing the item. This will often give you a better idea of the size and fit than a photo of it on a hanger or the carpet, and lots of sellers are happy to do this.

- Ask what the measurements are, and use a tape measure to work out the size of a similar item of clothes you already own.

- Do an internet search to find out whether the brand which made the item fits true to size.

- Ask the seller how they found the fit: they may be able to tell you whether they found it small or big compared to other clothes and brands.

- Try it on in a shop. Lots of sellers may be trying to get rid of items that they only recently bought because they got the size wrong or just found they didn’t like it. If you’re buying an item that is still available in shops, why not try it on? This can be great for buying only-just second-hand shoes – a great option for well-known, long lasting brands.

2. Have you thought about quality?

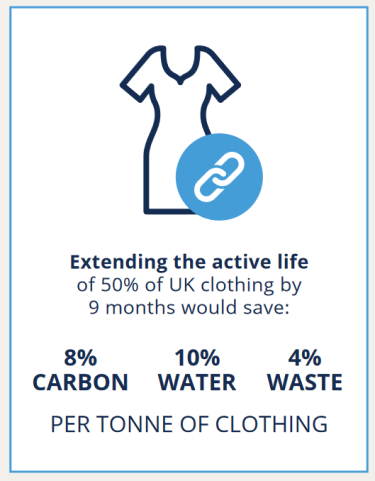

Extending the life of any item of clothing is good from an environmental perspective. However, you might want to think about the quality of your item from a value perspective.

Well-made clothing will keep its shape and last much longer than cheap throw-away fashion. It’s also less likely to look worn out from its previous owner.

There are a few ways to check the quality of an item.

Firstly, avoid well-known fast fashion brands like Boohoo or Pretty Little Thing. If you’re not sure whether a brand is fast fashion, check in our guide, or look at the prices on its website: if they look too good to be true, they probably are.

Secondly, think what brands you already know of that seem to make high quality clothing. Brands that charge a bit more can often be better made, although this isn’t always the case.

Thirdly, think about fabric: thin synthetic fabrics will often last longer than cotton, but they are less breathable and harder to recycle, so you may want to stick to natural fabrics.

Orsola de Castro from campaign organisation Fashion Revolution says, “The first thing to do when you’re looking at a piece of clothing is turn it inside out and pull at every piece of string you find. When clothes are cheaply made, the seams are often shabby. If it starts to unravel – don’t buy it.”

Quality will be particularly important if you’re buying a technical item of clothing, for example a second-hand waterproof or other outdoor gear. We talk more about this in our Outdoor Clothing guide.

3. Is it actually second-hand?

Recent years have seen a rise in second-hand clothing. Unfortunately, there’s also been a rise in people using resale apps like Depop to sell new fast fashion items at a profit.

Use the ‘Filter’ settings on resale apps or websites to make sure that the condition is ‘used’, so you don’t inadvertently end up buying new stuff that’s fuelling the fast fashion market. You may also want to check the other items on the seller’s page to make sure that they are generally selling second-hand.

4. Are there other ethical issues you want to consider?

For some people, buying second-hand is in itself the key ethical consideration. For other people, there may be certain additional ethical issues you want to consider. For example, some people may want to avoid animal products like wool or leather, even when second-hand, because it can normalise using body parts for fashion. Others may want to avoid synthetic fabrics because of concerns about the fact that they release microplastics into the environment when washed.

Some may also have concerns about certain second-hand retailers. For example, those concerned about animal testing may want to steer clear of Cancer Research and British Heart Foundation shops, two organisations that fund animal testing. (If you’re interested, the Victims of Charity website has a full list of charities which fund animal testing.)