Analysis: Changing Attitudes to Supply Chain Management

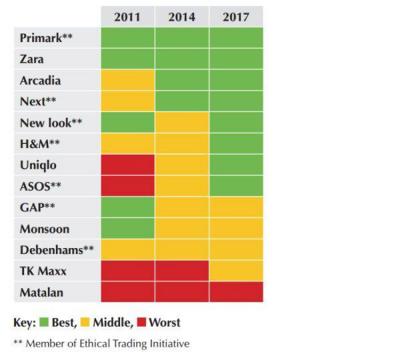

While researching for this guide, we were surprised to find that over half of the high-street retail brands investigated scored an Ethical Consumer best for their supply chain management rating. This was a huge improvement from 2011 when it was around 20%.

In fact, only two brands, Matalan and Amazon, now receive a worst rating in this category compared to nine receiving a worst rating in 2011.

We believe that this change has occurred for three main reasons:

1. High profile campaigns and consumer action

Campaign and research organisations – such as the Clean Clothes Campaign or Labour Behind the Label – have consistently produced reports detailing the horrific conditions which workers are subjected to in clothing supply chains.

These exposés have led many clothing companies to accept the need to take responsibility for what occurs in their supply chains as a matter of risk. In doing this, most high-street clothing retailers now produce corporate social responsibility reports, or at the very least statements, detailing their actions and policies addressing workers’ rights violations in their supply chain.

Recently, the campaign around increasing transparency has led to many companies disclosing their full factory lists – something campaigners have been asking retailers to do for years. M&S, for example, has an interactive supplier map on its website which allows consumers to look at where its factories are located, what they produce and how many people they employ.

Acting on these reports, the consumer is now making a big difference. In a crowded market such as clothing, the ability to distinguish a brand for its sustainable qualities appears to be becoming more important. In part, this is driven by the consumers who demand clothing which has been produced under fair labour conditions. However, it is also a reaction by big retailers that fear losing consumers, driving them to innovate and work with others to address issues.

2. Emergence of supply chain initiatives

The exploitation of people making clothes for major global brands and retailers has led to the emergence of various supply chain initiatives – all sharing the goal of rising working standards within the industry.

It is widely acknowledged that many of the systemic issues facing the clothing industry are not problems one company can fix. The need for collaboration between different stakeholders is key in driving the change needed to improving workers’ rights within supply chains.

One of the key organisations working in this space is the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) which was set up in 1998 by a group of UK companies, NGOs and trade union organisations. The aim was to build an alliance of organisations that would work together to define how major companies should implement their codes of labour practice in a credible way. 16 out of 21 of the companies in the high-street retailers’ product guide are members of the ETI.

However, the organisation is not without criticism. A report called “The Ethical Trading Initiative Negotiated Solutions to Human Rights Violations in Global Supply Chains?” challenged whether a voluntary initiative could be a replacement for legally binding mechanisms and found a significant accountability gap between companies committing violations and retribution within the ETI.

3. Regulation

Initiatives such as the ETI and others which focus on specific areas, i.e. Better Cotton and the Accord, can help to bridge a gap where state mechanisms fail. But the most effective tool in getting companies to at least report on their supply chains has come through regulation.

In 2015 in the UK, the Modern Slavery Act was passed which included a clause requiring companies with business activities in the UK and a turnover above £36 million to report on the actions they were taking to address the issue of slavery within their supply chain.

According to the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre its registry – the only free, public and transparent database of company statements – currently holds over 2,000 statements from companies in 27 sectors, headquartered in 31 countries.

Again, there are weaknesses within this regulation. First of all, there is no one policing the statements. The idea was that civil society organisations would rate and rank the statements which would help to drive forward change.

Some analysis by CORE has found that “only 14% of statements comply with the legal requirements and most provide little information on the six areas that the Act suggests companies may wish to report on.” Secondly, a company can legally produce a report which states it is doing nothing.

The Modern Slavery Act follows other regulations aimed at forcing companies to step up and demonstrate responsibility to people and the environment.

In 2012 the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act was introduced.

In 2016 President Obama signed into law the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act (the “Act”) which banned the import of “goods” produced using forced labour.

In February 2017, France passed a law requiring businesses with over 5,000 employees to conduct due diligence human rights abuses in supply chains.

By the end of 2017, EU member states will transpose the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive into their national laws, which will require about 6,000 large companies to report on Environmental Social Governance (ESG) matters including human rights.

Has this improved workers’ conditions?

Despite the rhetoric to change practices and respect workers’ rights, many of the brands are still facing issues which are systemic to the industry.

By way of example, a report released last year exposed the difference between practice and policy. SACOM conducted an undercover investigation inside four of Zara, H&M, and GAP’s supplier factories in China.

Despite the three brands’ CSR policies demonstrating commitments to workers and addressing issues within their supply chains, the investigation revealed the disparity between the brands’ supplier factory CSR Policies and the reality in their Chinese supplier factories.

‘Reality Behind Brands’ CSR – An Investigative Report on China Suppliers of ZARA, H&M, and GAP’ found examples of excessive hours, poor health and safety, low wages and no worker representation.

For many the answer lies in respecting and working with trade unions within the textile sectors.

Clean Clothes Campaign states: “Anyone serious about ensuring workers get a living wage and decent working conditions cannot ignore the role of trade unions. They offer the most effective and legitimate way to ensure that workers get a fair deal, by allowing them to stand together to defend their rights.”

Some brands have already started to make agreements with trade unions. In 2014, the Global Framework Agreement (GFA) between IndustriALL Global Union and Inditex was designed to promote decent work across the group’s vast supply chain, covering over a million workers in more than 6,000 supplier factories worldwide.

The Agreement “underlines that freedom of association and the right to bargain collectively play a central role in a sustainable supply chain because they provide workers with the mechanisms to monitor and enforce their rights at work.”

Tougher action needed

In conclusion, it is great to see that, at a policy level, companies are now beginning to address serious issues in their supply chains. The collective efforts of industry, civil society, consumers and governments are now having some impact. However, the extent to which this is impacting on the factory floor is still up for debate.

Companies need to be more proactive and work with international and local trade unions to ensure contracts are fairly negotiated.

What’s also missing is a more detailed legal framework for holding companies to account for continually failing workers in their supply chains. At present, beyond the bad PR, there are no real consequences for brands who do not live up to their responsibilities and this needs to change.