In this guide to dairy milk, we assess the policies and practices underlying UK milk brands.

We investigate whether ethical milk exists, if there are any ethical dairy brands, what makes organic milk different, and what animal welfare standards to look out for.

We also look at lobbying by big dairy brands like Arla and Müller and the role of supermarkets, especially around animal welfare and price, and how you can support local and higher-quality milk if you still consume dairy.

With growing awareness of the impact of livestock farming on the environment and climate, we also ask if any dairy milk is sustainable. Plus we have reviewed doorstop delivery brand Milk & More - and you may be surprised at their score (spoiler: it's not very high).

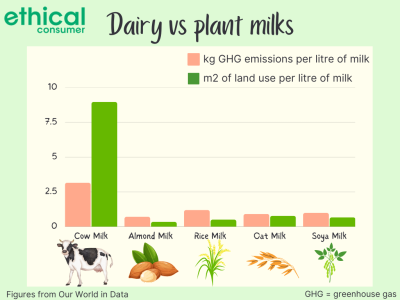

Our research into dairy milk recommends reducing dairy milk consumption overall, swapping in plant milks where you can, and going for the higher scoring brands in this guide if you can: these generally are organic and smaller dairies.

With brand scores ranging from an incredibly low 3 (out of 100) to 80, there is definitely room to find something better than milk from the brands languishing at the bottom.